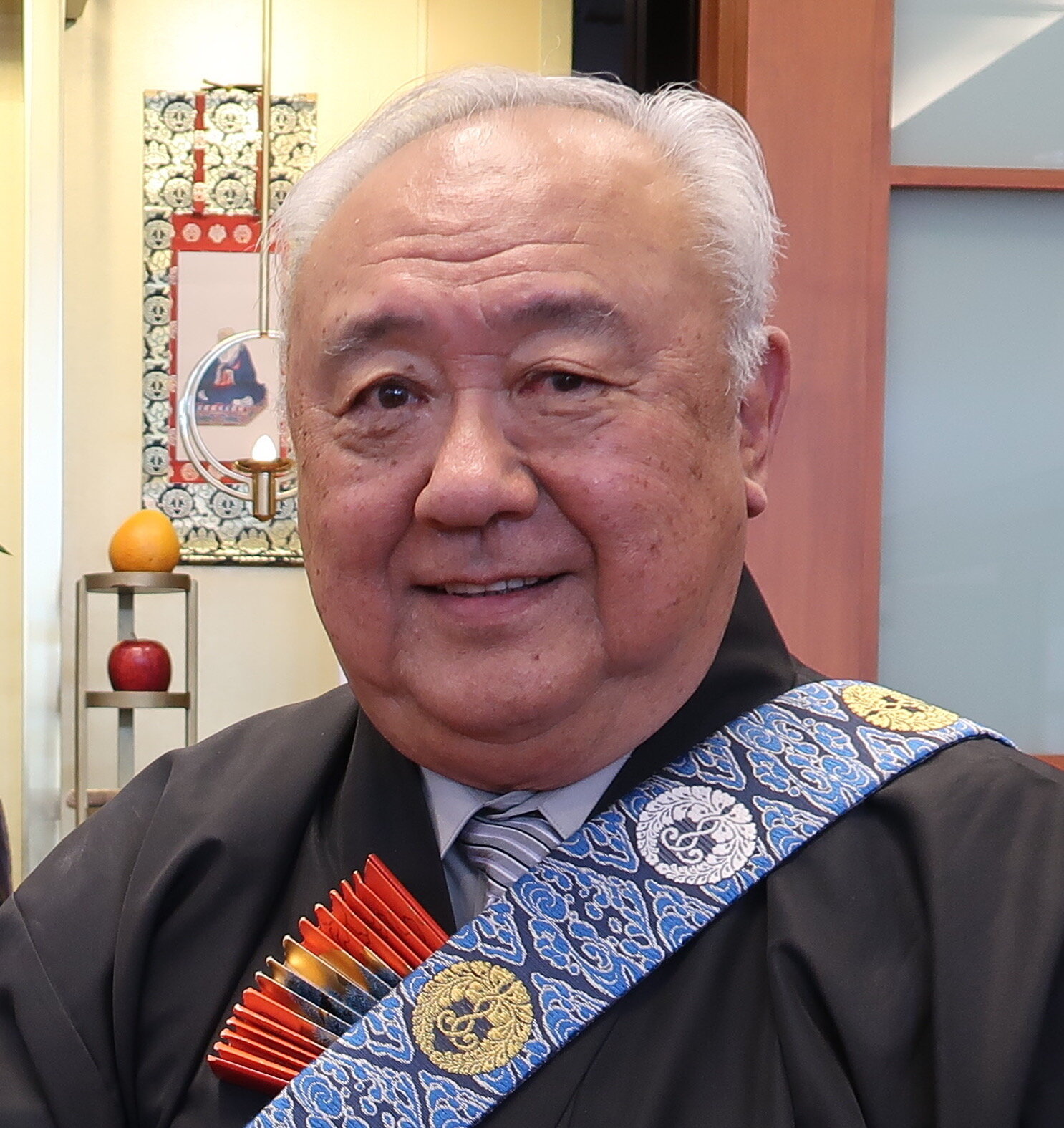

Rev. Bert Sumikawa

Windward Buddhist Temple

Hello, Dharma Friends throughout the Windward Side and beyond…..

Hope all is well for each of you and are keeping healthy and aware of Great Compassion surrounding us at all times.

Will you please join me in gassho as I read a passage from the Collected Words of Shinran:

Amida, full of compassion for those lost in the great night of ignorance------

The wheel of light of dharma-body being boundless---

Took the form of the Buddha of Unhindered Light and appeared in the land of peace.

Nano Amida Butsu

The Sanskrit word karuna is translated to mean any action that is taken to diminish the suffering of others, and a writer once translated this as “compassionate action.” It is natural to extend compassionate action or Karuna to everyone without distinction because we are all one.

As we help others and aid them in their healing process, all beings benefit. Because of the oneness of all beings, it is understood that Karuna is not only extended to others out of love, but also because it is an entirely logical thing to do. In the same way that you would want to heal your own wounds, you would also want the wounds of others to heal. In Buddhist literature, Karuna must be accompanied by Prajna or Wisdom.

Another Sankskrit word to describe compassion, is maitre, and in Pali, metta. The object of metta or maitre is loving-kindness. We all recite the Metta Sutta together at services every so often. What metta also means is love without clinging. What this means is that one must first cultivate loving kindness towards oneself, then their loved ones, friends, teachers, strangers, enemies, and finally towards all sentient beings.

Buddhists believe that those who cultivate loving-kindness will be at ease because they will see no need to harbor ill-will or hostility. It is generally felt that those around a person full of loving-kindness will feel more comfortable and happy, too. Radiating loving-kindness is thought to contribute to a world of love, peace and happiness.

Compassion is often likened to the ocean, where the swimmer is lifted and supported by the ocean. In Jodo Shinshu, compassion is like the ocean which supports and uplifts you.

Many of you recall the story of the swimmer who struggles against the swift current, only to find that by letting go of his struggle, the ocean itself will take him safely back to shore. Doctrinally, this compassion is expressed as Other Power, or Amida’s Vow.

Some temples recite the Sharing Loving Kindness passages or the Metta Sutta, which is our deepest aspiration or hongan for the world around us. The word hongan is made up of 2 sanksrit words; Hon (Skt. Purva) meaning, “basic,” “original,” or “primal” and Gan (Skt. Pranidhana) which means “desire” and “vow.” When used in this way, it has universal implications, belonging to all beings.

In the Sharing Loving Kindness Metta, it starts out by caring about ourselves and then it goes on to include our family, friends and then to those who are not nice or kind to us. Finally it includes all beings, human or animal. It is our wish that all are happy and well, and are never angry, hurtful or jealous and may all live in peace and harmony.

So in the practice of meditation on loving kindness we recite specific words and phrases in order to evoke this “boundless warm-hearted feeling.” It is a tool that permits one’s generosity and kindness to be applied to all beings. The result is having to express true happiness in another person’s happiness and true sorrow in another person’s sorrow.

There was a story in the Honolulu Star Advertiser entitled, “Neither society nor the system should give up on any single kid.”

It said that nation-wide, troubled kids are pushed back into the background, and that there is little sympathy for these young people, with the public seeing them as nothing more than smaller versions of adult criminals. They are not mini-adults, and their brains are still developing and sometimes have little control over their lives. But they don’t choose their families, they don’t choose where they live, and don’t decide on their DNAs. They also don’t choose their early childhood experiences that sometimes can be very traumatic. Every decision is made by an adult, so in essence, their failures are our failures.

Several legislative proposals were written to address these failures in the right way. Bills to appropriate funds to the Family Court system to reduce juvenile delinquency through evidenced-based practices, and mental health and substance abuse treatment programs are bring put forth. Although these youths must be held accountable for their actions, they are also at the same time, victims too.

In spite of the odds against them, they all have the potential to live a healthy and productive life. Neither society nor the system should give up on them. Their deep wounds can be healed, with a compassionate heart and a caring hand.

At this time, I want to talk about the Buddha’s Compassion. Compassion is the fundamental spirit of Buddhism and is the central to the practice of Buddhism. The bottom line of the religious practice is that there must be consideration and empathy to others, animals, plants and nature. In talking about the Buddha’s Compassion, I would like to relate this story to you.

There was a couple in Shiga, Japan that wanted to have a baby for a long time and finally the wife became pregnant. They were very happy. However, shortly after birth, the baby became critically ill with a very high fever. When the baby was wavering between life and death, the parents wanted their baby to live more than anything else. They really thought so. They even wanted to give their lives in exchange to save the baby. Fortunately, the child survived that ordeal, but unfortunately, the child also suffered extensive brain damage due to the high fever. Weeks, months, and years passed and the child was not able to talk or walk. Gradually, the love the parents once had for their child started to change because of the difficulties they now had to cope with. They began to feel that it would have been better if the child had died earlier, so that both the parents and child would not have to suffer.

The parents could not accept their child anymore. They believed that the ability to be a normal child was necessary for their child’s happiness. Sad as it is, this is the reality exposed to us by the Buddha’s Compassion. When so much importance is placed on our abilities, we feel our lives are worth living only when we have those abilities.

Was the child accepted? We can say, “Yes” by receiving the teaching of Buddhism. In Buddhism, the child is completely accepted. In contrast, judging a person by their ability is just an example of our egoism. Everyone has a life worth living in their own way, just as they are. Everyone should be accepted as they are.

When we were born, we were all welcomed by our parents and appreciated as we were. Buddhism teaches us that we have to return to these original feelings. To practice compassion is to accept everyone as they are. You are OK as you are, they are OK as they are.

Buddhism also asks me, “How about me? Am I accepted as I am?” Yes, as I was taught, I am accepted as I am. However, doesn’t the phrase “accepted as I am” actually mean discovering who I am? Buddhism teaches me that I am the one with false pride and an ego-self full of feelings of discrimination. I am the one wanting to judge others, but unwilling to judge myself, finding faults in others, and finding excuses when I do the same things. But this “I,” even as imperfect as it is, is accepted by the Compassion of the Buddha. When we realize our true nature, we can bow to the world we live in. We can be humble and take a new, dynamic step forward in our lives. When we see our true selves, helping someone in need comes naturally.

Once, when asked what religion is the best, the Dalai Lama replied that, “Whatever makes you more compassionate, more sensible, more detached, more loving, more humanitarian, more responsive, more ethical. The religion that will do that for you is the best religion. I am not interested, my friend, about your religion or if you are religious or not. What is really important is your behavior in front of your peers, family, work, community and in front of the world. Remember, the universe is the echo of our actions and our thoughts. Take care of your thoughts because they become words; words because they become action; actions because they become habits. Habits will form your character; character will form your destiny; and your destiny will be your life.

There is a story in the Jataka Tales ( tales about the Buddha in his past lives, somewhat similar to Aesops Fables) and it is about a compassionate king, a hawk and a dove. One day the king, as he was taking a walk in his garden came upon a dove that was bleeding. Feeling sorry for the dove, the king ordered his retainers to go and get some medicine for the dove. A hawk then flew up and asked the king if he saw a dove fly by. The king replied that he did, and that the dove was injured. The hawk said that well, it was his dove and that he had gone a long time without eating and was starving to death. Even though I was weak from lack of food, I pounced on it and injured it, but it got away. Please give it to me, it’s my dove. But the king answered that the dove came to him crying, “save me, save me.” How can I hand it over to you and have you kill it and eat it? There must be a dead bird around somewhere for you to eat. “The meat of a dead bird will not save my life, give that bird to me.” You may think you are compassionate to save the dove but saving the dove means killing me. If I cannot eat the dove, I’ll soon die. The king thought about this for a while and thought that he cannot let the hawk or the dove die, so he decided to let the hawk eat his flesh instead. Fine, said the hawk, any fresh meat is fine, and a small dove will save my life so give me a tiny bit of your flesh to eat. So the king had a scale brought to him, weighed the piece of his flesh and then the dove, thinking that for sure his flesh would surely weigh more than the dove. However, the dove’s weight was much heavier than the flesh.

Seeing that, the hawk thought that humans will cheat to protect their own lives. However, the king cut another chunk of his flesh as big as the first and placed it on the scale thinking that for sure now it should weigh more than the dove. But, the dove was still heavier. The hawk asked, “What will you do for me?” The king answered that he understood and got on the scale himself. Lo and behold, the scale balanced and the king and the dove weighed the same. So to save the dove and the hawk, the king offered himself to the hawk.

So you ask, how can the king and the dove weigh the same? The message of the tale is this: that the lives of the dove, hawk and the king had the same value. This tale conveys the message that the value of a life cannot be measured by status, physical volume or weight. Buddhists believe that the lives of a hawk, a dove and a king all carry equal weight. Stories such as these help us to understand the meaning of life.

Through the Wisdom and Compassion of the Buddha, we learn to appreciate everyone, just as they are, just as I am.

So let us reflect on these thoughts as we read a poem written by Rev. Hiromi Kawaji entitled, “Boundless Love.”

There is sweet serenity

In Amida’s boundless wisdom.

There is much warmth to be found

In Amida’s robe of love.

There is wholesome nourishment

In Amida’s divine food;

Let us cherish the freedom

To live this wondrous life;

A life full of boundless joy,

With passionate gratitude.

Thank you, and now please join me in gassho as I read the words of the Buddha:

The spirit of Buddha is that of great compassion and loving kindness. The great compassion is the spirit to save all people by any and all means. The great loving kindness is the spirit that prompts it to be ill with the illness of people, to suffer with their suffering.

“Your suffering is my suffering and your happiness is my happiness,” said the Buddha, and, just as a mother always loves her child, he does not forget that spirit even for a single moment, for it is the nature of Buddhahood to be compassionate.

Namo Amida Butsu